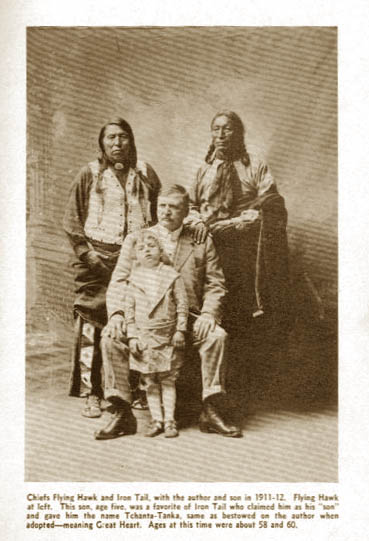

| Chiefs Flying Hawk, at left, and Iron Tail with the author and his son

in 1911-12. This son, age five, was a favorite of Iron Tail who claimed

him as his "son" and gave the name Tchanta Tanka, meaning Great Heart,

the same as bestowed on the author when adopted by the Sioux. The

chiefs' ages at this time were about 58 and 60. |

A Sioux squaw in full dance dress |

As the sun went down in dark clouds fringed with

orange and gold, and the twilight cast long shadows from the rugged

western hills, the strange scene gradually faded and darkness

spread over it all. Flash lights and torches appeared and camp-fires

were showing all around, like myriad fire-flies flitting about in the

gloom. A faint roar like the hum of a distant cataract could be heard,

broken by the shouts of the herder-boys as they made their nightly

round-up. Here and there could be heard the tom-tom and uncanny

war-songs of the weird dances and feasts being held in various sections

of the great encampment.

As the sun went down in dark clouds fringed with

orange and gold, and the twilight cast long shadows from the rugged

western hills, the strange scene gradually faded and darkness

spread over it all. Flash lights and torches appeared and camp-fires

were showing all around, like myriad fire-flies flitting about in the

gloom. A faint roar like the hum of a distant cataract could be heard,

broken by the shouts of the herder-boys as they made their nightly

round-up. Here and there could be heard the tom-tom and uncanny

war-songs of the weird dances and feasts being held in various sections

of the great encampment.Alone on the hill, in the darkness, came the thought that gradually grew into conviction—here was about to open the curtain on the last act of a great world drama. This great conclave had gathered here from all the country round; they came from Kansas, Oklahoma, Utah, Colorado, Wyoming, Montana, Idaho, Nebraska and North and South Dakota;—they came in wagons, worn-out Fords, and some by train from distant points. They had their camp equipment, food, clothing and regalia, with forage for their horses and ponies, with barrels of water for use in camping on the dry and dusty trip over the arid plains and desert country. It was for them an event of a lifetime, and they came and conducted themselves accordingly. There were few whites present. It was a hard journey for them with their esthetic tastes and habits. It was Indian country, and the government furnishes accommodation only for its employees. In the center of the big camp grounds had been erected a sun dance pole about forty feet high, to which, about half way up, was attached a bundle of brush with green leaves on the tips, which formed a sort of rude cross. Surrounding this pole, and a hundred feet distant from it, was a double stockade of tree-trunks set on end and connected at the top with smaller but similar materials, and over all were spread green boughs, making a kind of canopy, in the shade of which the older people and guests could sit to watch the performance carried on within the circle. From one-thirty to four-thirty, or sundown, each day for four days, the ceremonies were performed. Twelve men and five women took part as principals in the sacred sun dance; they dressed in most grotesque costumes, but remained naked from the crown to the waist-line, which they painted in hideous and fantastic colors. Music for the dancing was furnished by seven old men aged seventy-eight and over, led by Lonefeather, who carried a "discharge" from government scout-service in the late seventies. To the accompaniment of the weird yelps and chanting of these old men they tapped a big bass drum with muffled sticks, around which they squatted in a circle while the drum lay flat on the ground between them. Each day, on opening the ceremonies, some noted chief would make an oration. One, by Pretty Bird, was strikingly like a Roman Senator as pictured in classic paintings. He stood more than six feet in height and, with his blanket draped about his shoulders as only an Indian can carry one with grace, his attitudes and gestures, as well as his language and delivery, were superbly impressive. The President of the Indian association sponsoring the big event was William Spotted Tail. He was son of the celebrated chief of old days who was assassinated by Crow Dog, whose daughter Walking Crow Woman, was present to join in the celebration. She was about seventy and, when encountered in the Pine-Ridge-section village, she was engaged in preparing a puppy dog feast. On hearing the click of the kodak she became indignant and threatened the intruder with dire consequences. But when she discovered that he was a member of her own tribe, she relented and invited him to the banquet which would be ready at dusk. She told the story of her noted father and brought out from her tepee the knife he had used in lifting the scalp of the famed chief at Rosebud. It had thirteen notches on the handle—record of his bravery in the troublous war-times. She exhibited her grandmother's valued wampum belt of beads, some of which were the crude iridescent ones turned out by the Mandans described by Lewis and Clark who stayed with them over the winter in 1804; others were specimens from the Jesuits' visits in the early exploration days. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

| previous page | table of contents | next page |

|

|

||