|

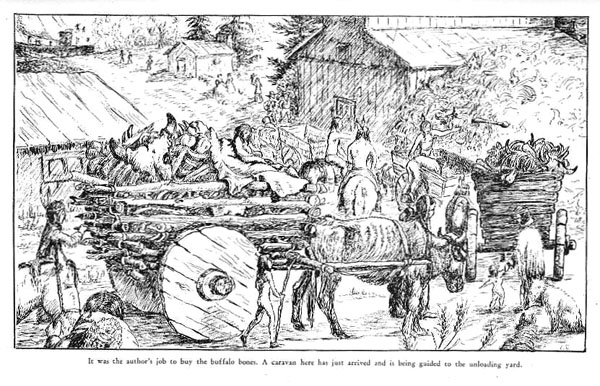

It was a picturesque theater, this meeting place of the red and white

races on this last frontier, when the red folks came in from one of

their bone hunting campaigns. Led by the chief on his pinto pony,

carrying his feather-streamed wand and with beaded moccasins on his

feet, a few eagle feathers dangling from his scalp lock and his

bead-bordered blanket draped gracefully from the left shoulder or

girded about his waist, the mile-long procession was seen and heard far

out on the prairie as it dragged its way along like some great

pre-historic serpent. They were coming to trade--not beaver skins, not

the soft furs of the otter, mink or silver fox, as once was their stock

so coveted by the white adventurers of old, but the whitened bones from

the decaying skeletons of buffaloes which had been ruthlessly

exterminated by the white men but a year or two ago. Buffalo was their

food, their clothing and their shelter from the wicked winter weather;

they now brought the only thing left for them to barter for food and

cloth, in the vain effort to save themselves from starvation. The

motley cavalcade approached to reveal a hundred crudely constructed

wooden high-wheeled carts piled high with relics of the white man's

abattoir. To each hand-made vehicle was harnessed a cow or bull or

scraggy steer, harnesses of rawhide without buckle or thing of brass or

metal of any kind, just as the carts were made without tires, bolts,

screws or iron of any kind; now and then a pony tugged in the cumbrous

shafts to pull its load, four-fifths of which was comprised of the cart

itself. On top of the cargo was perched the bead-covered pop-eyed

papoose of the squaw encased in the tepee cover belonging to the

family, while the squaw herself with another strapped to her back,

walked alongside to guide the pony and saw to it that her dogs, needed

for puppy-stews at camp, did not get too far astray. The men astride

their ponies brought up the rear; they carried the guns and

occasionally succeeded in bagging a grouse or antelope with the

single-barrel trade short gun or discarded army carbine, for the

evening camp-stew. They came close to the white man's settlement and

pitched their lodges just north of the border street. Here the tepee

poles and coverings were discharged; the women and children, the extra

dogs and ponies collected together with the camp equipment, and the

women erected the village while the men proceeded to guide the long

procession through the street and over the weighing scales where each

driver was handed a ticket showing his number and the gross weight of

the load belonging to him. After unloading at the railroad bone-yard

the return of empty carts passed through the same ceremony of weighing

when the net weight was written on the tickets making them available

for trade or cash at the white man s store. The long dreary journey

known to have been, on more than one occasion, one hundred and fifty

miles from the gathering point, these families of red and mixed-breed

now prepared for two weeks of trade and recuperation. The proceeds of

their loads of bones netted them from two and a half to five dollars

each and with the earnings of the women and girls as charwomen or hotel

kitchen help, they were able to live comfortably while the camp lasted.

Billy Oswald and Pat McWeeney both were frequent visitors at the Indian

village and they delighted to scatter pocketsful of nickels amongst the

little red folks and to watch them in their mimic war dance and to

compete for prizes with their bows and arrows. Also Annie Gray

accompanied by Girtie or May were frequenters of the Indian camps, and

always they carried packages of fruit and candy and cakes for the

papooses, and used dresses, gloves and dress materials for the squaws

and girls. Ten days or two weeks saw the break-up of the camp and a

month of quiet passed over the Indian grounds until this or a similar

band came to repeat the visit. |

|

And these skeletal remains of the vast herds once roaming the great plains country from the Rio Grande to the British border were similarly gathered by the natives and early pioneers before and subsequently until there had been accounted for the respectable total of forty million dollars worth. The bones so collected and sold represented more than fifty million of these noble animals--a mere fraction of the total number brutally slaughtered in the name of sport or for the paltry sum to be obtained for the skins while the valuable meat was left to feed the coyotes, wolves and buzzards. Like the wild pigeon, the buffalo were exterminated as wild game without consideration for the future and it did not take long; for two hundred and fifty thousand buffalo hides were shipped from a single railroad station--the result of one season's campaign of the insatiable hide-hunters. At the south shore of the lake, on the Fort and Indian Reservation, the Sioux had collected near the boat landing, a huge pile of bones in readiness for shipment when the railroad made connection with the boat landing at the north shore. At the west end of the lake, another great stack of them had been dumped awaiting the arrival of the branch railroad, then pushing north from the main line of the Northern Pacific. During the days of first settlers' struggle for best locations and the passing of the hordes of immigrants in search of homesteads in the open country beyond, Billy's "Gem Saloon" prospered and Annie Gray came to live at the house newly erected half way between the elevator and the boat landing. When Pat came to the townsite in a bobsled, two women accompanied him--Kit Brennan and May Munson. Pat built himself a bungalow frame house on his lot on the north side adjoining the Indian camp grounds where after the usual frontier ceremony, Kit was installed as a life partner; then the town burgess, Olaf Hanson, appointed him the town police. May Munson was young, bright of eye, well-formed with dark hair and red cheeks and without experience in the rough environment she found herself. Notwithstanding the watchful oversight of Kit, May was promptly christened the "town peach" and the contest for her favor was unanimous on the part of the male population. Handsome Billy Oswald made her his special mark, and in due time won the prize, for when Billy came, she was living at the Lake Hotel where he registered. Not, however, was he successful until one midnight late in June the hotel was found to be ablaze. Billy rushed in, broke down her door, caught her up in his arms from sound sleep, kissed her passionately as he ran with her into the street, where together they watched the total destruction of the town. May's life was saved, but that was all, for in the high wind, every structure in the town was swept away like dried grass in a prairie fire. Daylight saw a prostrate community; homeless, but far from hopeless. Soon they contrived flimsy shelters from the limited stock at the lumber yards and a few army tents borrowed from the fort. Meanwhile, the railroad brought in food supplies and great quantities of lumber and a new town sprang up like magic. First among the new and better structures was Billy's "New Gem," which provided a comfortable upstairs apartment for the temporary home of Kit and May, and here Pat did what he could to make them comfortable during the while that Billy's patrons at the rough bar below made bets that Billy would win the favor of the beautiful "Peach." |

|

|

||

| previous page |

|

next page |

|

|

||