"Nature Produces Nothing for Nothing"—-Mandan Indian, 1806

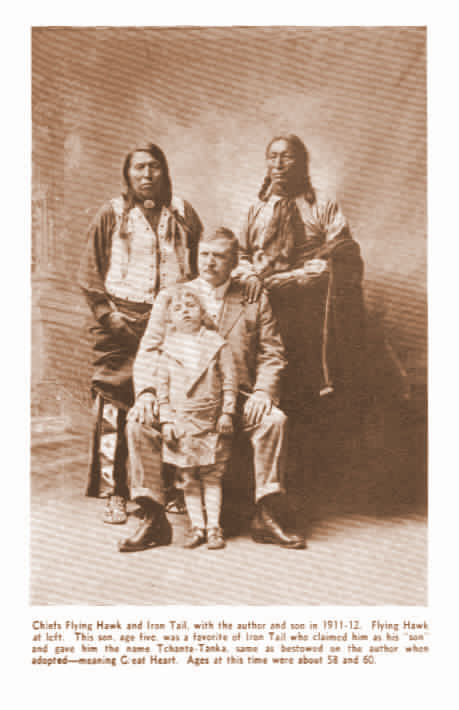

"Nature Produces Nothing for Nothing"—-Mandan Indian, 1806 BUFFALO BONE DAYS A SHORT HISTORY OF THE BUFFALO BONE TRADE A Sketch of Forgotten Romance of Frontier Times THE STORY OF A FORTY MILLION DOLLAR BUSINESS FROM TWO MILLION TONS OF BONES BY M. I. McCREIGHT (Tchanta Tanka)- A Last Survivor, Bone Buyer and Shipper COPYRIGHT I939. BY M. I. McCREIGHT ALL RIGHTS RESERVED PRINTED BY NUPP PRINTING CO., SYKESVILLE, PA |

| Indians unloading Buffalo Bones, 1885, at Devils Lake, Dakota Territory |

|

|

The Covered Wagon, the Pony Express, the Mormons, Pike's Peak and the Forty-Niners occupy full place in United States history, but where can one find the story of the Buffalo Bone era? Buffalo Bill made the American and most other nations familiar with the killing of buffalo, but the extermination of the herds for their hides and the consequent sacrifice of original proprietors of the vast interior of the continent, is a stained page present-day American citizens wish might be omitted from the final volume that coming generations must read to learn the story of the spread of civilization toward the Pacific. The middle of the nineteenth century found the Indians and the buffalo crowded to a line roughly defined by the main stem of the Mississippi between the Wisconsin and the gulf. Westward of that line from Manitoba to the Rio Grande was the Indian and buffalo country, to the Rockies, and beyond. The upper or north section of this vast region was recognized as the Sioux Country; however, it was occupied by other tribes including the Crows, Shoshones, Cheyennes, Blackfeet, and as the more southern section is considered, we find the Arapahos, Utes, Pawnees, and Comanches and Omahas. Indian Territory held the remnants of eastern tribes placed there by the Government. This section, now the state of Oklahoma, was then the home of the Creeks, the Cherokees, Choctaws, Delawares, Shawnees, Osages, Poncas and others, as it still is. Nature, by her wise provision of changing seasons, provided likewise a change of pastures for the myriad buffaloes that ranged from winter feeding grounds in Texas, northward, as the green vegetation came with the melting of the snows. By midsummer these great herds would be found in the upper Missouri country when, like the wild geese, they would turn about and graze to the south again as cold weather came on them where blizzards raged across the bleak prairies and snow covered the pastures deep for months. Detached herds and stragglers were left behind and had to paw away the snow to reach the dried grasses and subsist through the winter in sheltered places on streams or in the foothills, as best they could. It is almost inconceivable to the present-day mind, the great number of animals that covered the plains country from Canada to Mexico in the time of their free range. Estimates have been recorded from one billion down to a hundred million, at the period of the early seventies. Yet it must be remembered that it was a big country, and a hundred million animals scattered over a thousand miles by five hundred miles in area, would after all, seem a very few. E. A. Brininstool, in "Fighting Red Cloud's Warriors," refers to an estimate, made by General Phil Sheridan and his staff officers, of a section one hundred miles square through which they had just passed south of Dodge City; their first calculation of the animals seen on that trip, was one billion, and later calculations much reduced finally resulted in making it one hundred million but they were afraid to announce the figures for fear of being charged with deliberate misrepresentation,—yet they believed the figures entirely too low. During that period, it was not uncommon to see herds of twenty to forty miles in width and of unseemable length, massed as closely as they could move. Col. R. I. Dodge states that he drove through a herd twenty-five miles in width and of equal or far greater length. The building of the Union Pacific in the late sixties was the beginning of the great slaughter; hordes of ruthless hide - hunters rushed into the range country to join in the grand extermination campaign, when tens of thousands of the shaggy brutes were killed for the fun of it. Only the hides were taken, if convenient to deliver them for sale at a dollar each, and the carcasses were left to the wolves and buzzards, and their bones to become a vast sepulchre over the wide plains. The Kansas and Nebraska country became a wilderness of whitened skeletons. The Santa Fe towards the southwest was but a repetition of what had taken place in the Platte and Republican river sections, as was also the pushing of the Northern Pacific railroad into the up- per Missouri country. With the extension of the railroad to Dodge, goods were freighted by teams and wagons into Texas, and it was these returning empty freight caravans which gathered up the buffalo bones and piled them at the Dodge terminal on the prospect that a demand might be developed for them by fertilizer factories. Such a market did arise in due course and considerable sums were thus secured by the thoughtful teamsters, who are said to be the originators of the buffalo bone trade. Whether or not the business was begun here and in this manner, it is for Major Inman to report that front 1868 to 1881 more than two million five hundred thousand dollars was paid out for buffalo bones in the Kansas section alone; his figures, used in Brininstool's book, show that this tonnage accounted for thirty one million animals. If we take Major Inman's count for the thirteen years from '68 to '81, we must also assume that gathering of bones began in 1868 and was completed by 1881, in the territory served by the Kansas Pacific-Santa Fe railroads in that district. But that by no means indicates that all the bones had been collected in the Kansas-Nebraska country during that period. Main and branch lines were being pushed out in many directions and the settlement by incoming pioneers continued for many years,—and likewise the gathering of bones followed until the entire farming area of the two states, was under cultivation. It is fair to assume that bone collecting in the Kansas section continued for at least four years beyond 1881 even though on a less pretentious scale, therefore to arrive at a fair estimate on the total for the Kansas field, we may add to the figures of Major Inman at least another million dollars, in doing which, we have a total sum of $3,500,000. During this period, the state of Nebraska was being settled and it was also a buffalo country, though perhaps, not so good a grazing land as was Kansas. We have no dependable estimate of the buffalo bone traffic for Nebraska, but we do know that the business was conducted in that state's area, in the same manner and for the same reason, although perhaps not so large a scale, as was done in the adjoining section at the south. It would be permissible and eminently fair to place the estimate for bones collected and shipped out of the Nebraska region, at $2,000,000 at least for the same period. With these calculations, it leaves for further consideration, the great areas included in Oklahoma and Texas on the south, and South and North Dakota, Wyoming and Montana on the north, for they were all buffalo country. In order that the reader may grasp a better appreciation of the speed with which these countless herds of native animals were exterminated and furnished the raw material for the industry of buffalo-bone traffic, let him picture the tens of thousands of discharged Civil War soldiers who flocked west for a chance to make a living; the thousands of trappers, traders and professional hunters; the gold seekers and adventurers and the rum peddlers and those who sought work or pleasure on the general movement to get a foothold in the exciting frontier; they were a human flood, which, like a broken levee, overflowed the Indian country, and as conquering hosts, swooped down on the helpless buffalo herds and annihilated them as if they were a vile vermin instead of a highly valuable natural resource. In the middle 70's it was not uncommon for the lone still-hunter to shoot down 150 or 200 without moving from his hiding place. One man claimed to have killed 1500 buffalo in seven days, and that he killed 250 in a single day; another is quoted who said he shot down 120 animals in forty minutes, and it is claimed that nearly four million animals were killed and their hides shipped out over the Santa Fe railroad, while the carcasses were left to rot on the plains—all in two years. When one contemplates that this kind of slaughter was going on at like rate from the Canadian border to lower Texas it is no wonder that it took but a few years to exterminate the nation's entire herds of the bison; the same kind of sportsmanship and the same kind of people exterminated the carrier pigeon, which we once possessed in the same quantities, and now would pay fabulous sums to recover them. |

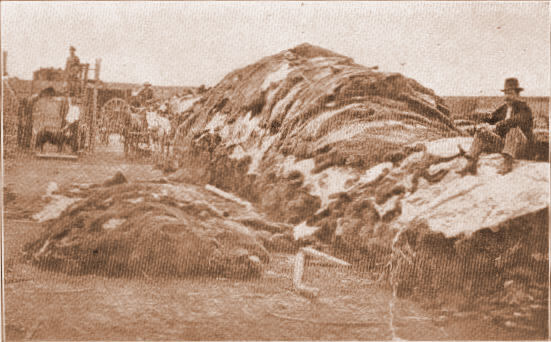

| Forty Thousand Buffalo Hides in the corral of Wright & Rath, Dodge City, Kansas |

|

|

Compilations rendered by the Santa Fe show that during the three years

1872-1874 that railroad shipped from points on its lines in Kansas

459,453 buffalo hides, and 10,793,350 pounds of buffalo bones, and from

other lines in tile same sections and for the same years, there were

shipped out 918,906 hides and 21,586,700 pounds of buffalo bones. It is

to be regretted that similar official figures cannot now be obtained

for the trade of Oklahoma, Texas, Nebraska, Colorado, Wyoming, and the

great area included in the states of Montana and the Dakotas. Some

twenty-five years ago Mr. James J. Hill was appealed to for data of

hide and bone shipments over the northern lines, but fire had destroyed

the railroads' records covering the period of buying and shipping hides

and bones out of that region, so that only the data furnished by a St.

Louis carbon works, one of the larger users of bones, could be found

then from which estimates could be reliably made. State Historical Societies for these various commonwealths have been searched for local records, but little can be discovered to assemble accurate information which would offer authentic figures for the total of such a vast and scattered industry. Enough is known, however, to show that, while no mention is made of it in U. S. history, it was a business of great magnitude and amounted to many millions of dollars, and had a far-reaching effect in the "Winning of the West." It is now more than half a century since the writer was engaged in the business of buying buffalo bones in the Northwestern frontier when the trade was at its zenith. In the effort to gather official data regarding it, with the hope that historic record might be made for the benefit of future generations, it was to learn that no one can be found who knows anything about it. Finding himself to be the only likely survivor of that interesting trade and economic epoch, the obligation to furnish the story of his own experiences and what can be supplied from other sources, this little sketch is written with the hope it will fill somewhat the gap now existing in the story of our exploitation of our native tribes and the spread of our boasted civilization over the great Mississippi - Missouri country. It was over fifty four years ago that the writer stepped down from the platform of the local train at the end of the track on the frontier of north-central Dakota Territory. The first persons to meet and greet him was a small band of Sioux Indians who had come, in their gala dress, to witness the coming of the wonderful fire-wagon; they were a fine healthy lot; and as the travel- worn youth with his carpet-bag and lunch basket looked about for someone from whom he might ask directions, the chief stepped up and with extended hand, said: "how cola." Half in fright and with a puzzled hand-shake, the boy made his way toward what seemed to be the white man's town, he passed by a large pile of bones, and wondered what it meant. It was not many days until he was informed, for soon he found himself in full charge of the business of buying and shipping buffalo bones including the very pile which had so aroused his curiosity on arrival in the far west;—for this was Indian and buffalo country then,—but it proved to be the end for both shortly thereafter. It was the last year for the buffalo; and it was the last year of the happy, healthy, life for the Indians. With apology for seeming egotism the writer here explains that he was a business college graduate with two years' training in merchandising and banking when he got the western fever and went to the jumping-off place to get acquainted with the Indians. Indians had killed his own great-grandfather and carried on a war of extermination against his forbears in Pennsylvania in the old days. That kindly greeting by the old Sioux Chief quickly dispelled much of the prejudice that had filled his heart through childhood, and soon the youth began to think that Indians were not such terrible folks as Eastern people believed they were. In looking out for a job, the pioneer stockman and contractor was appealed to. He said: "What kind of a job do you want, my son?" The boy replied: "I can do anything you have to do, sir !" Then, said the stockman: "Suppose you take care of my racing mare and get her in condition to enter the race in Jim Hill's Fat Stock Show next month"—and they walked toward the stables where instruction was given for feeding, rubbing down, watering and exercise. It was feed-time in the evening, and the boy went to work, for he had been raised amongst horses, and knew his duty. At bedding-down time the owner stuck his head in the door to see what the boy was doing toward making good at his job—and he found him busy with wisps of straw rubbing down the shiny legs of the racer, which by the way, in the east, would have been classed as merely a good buggy horse. "Young man," said the contractor, "where did you come from?" "Pennsylvania, sir, was the reply. "What did you do there?" was asked. "Run a bank, sir" the boy replied. "Can you keep books —double entry books?" was the next question from the stockman. "Yes, sir, that's my business, I can keep any kind of books, and I have a diploma and two years' experience, and a letter of recommendation from the banker for whom I worked, sir" the boy replied. "Then come to my office in the morning at seven o'clock" the man said, as he left the stable. Morning found the two in the lobby of the substantial brick store room, one corner of which was enclosed with a glass partition behind which was the office desk, safe and book keeping equipment. "This is your office from this morning; here is the combination of the safe; here are the firm's books and you will get anything else you need; come with me to the bank and file a signature for signing checks," and instantly that duty was fulfilled; the banker was told to see that the young man got what he wanted when he wanted it, then turning to the youngster told him to board around the different hotels, and to begin with, the salary would be fifty dollars a month; and went on to his business of buying cattle, for he was the head of the firm, and outside-working partner; he was Sam Dodd. The inside and office member of the firm was Johnny Moore—a jolly Englishman, as fine a man as ever lived, and a pioneer from the Pipestone country of Minnesota; they had married sisters and had emigrated to the frontier among the first, to join in the development of the new country opened by the extension of the St. Paul, Minneapolis & Manitoba Railroad; they had opened a live-stock and meat marketing business and secured the contract for supplies to the Garrison at Ft. Totten, Indian Mission, Post Traders, etc. And there were whisperings of the possible extension of the railroad into the Mouse River country a hundred miles farther west. A survey of duties which would fall to the young man, was found to be formidable enough; they included installing of a new and modern double entry system of accounting; the handling of all finances, buying of cattle for market use; semi-monthly trips to the fort to collect bills from troops, traders and teachers; time-keeper and paymaster for the 12 to 20 outside employees as well as for the cutters, teamsters, drovers, cowboys and corral and stablemen and caretakers. And then one day smiling Johnny came in and said to the busy cashier: "Mac, it will be up to you to take care of the 'breeds and Indians when they come in with their buffalo bones"—and so another but very interesting department was added to the regular routine work of the greenhorn youth. He was now twenty. To paint a word picture of that country as it then was, makes a vastly different one than if made today. It was then in its natural state— a wide open prairie extending from the Red River of the north, westward to the broken lands of Montana, and it was the last of the great buffalo ranges. On the maps of the early day school geographies it was designated as the "great salt water region" —just as the western parts of Kansas, Nebraska and Texas, were noted on the maps as the "Great American Desert." At the break-up of winter a large proportion of this land area was covered with water, which by summer months gradually settled into hundreds of lakes. Without inlets or outlets, these shallow lakes became more or less stagnant and with the constant seasonal evaporation, became alkaline—hence the name, "salt water region." To illustrate what a profound transformation took place in the North Dakota country, the story of the old buffalo-hunter, as related to the writer, is here repeated. He said that he had accompanied a Government expedition over that section twenty years earlier, and that they were obliged to pole their way in canoes from the Red River to Minnewaukan lake, with two or three short portages. He said that their report was made showing the whole region to be wilderness of lakes and that it was useless for agricultural purposes; that it was uninhabited, and was a paradise for wild birds, buffalo and antelope, with a few straggling bands of Indians on the higher grounds and in the fringe of woods which then stood about the larger lakes. The old hunter told about joining with a band of Sioux under the famous Chief Standing Buffalo, in the regular fall hunt on the north shore of Minnewaukan; he said the Indians made a surround driving the herd and holding it together in compact form near to the lake border. There they were kept quietly under control until the ice became sufficiently strong to bear the weight of the animals, but before it became covered by snow —and then the grand rush was made by the Indians, driving the helpless and frightened brutes onto the glittering surface where they could not but submit to sudden death from the onslaught of hungry savages. He pointed to the bay which then was but a short distance, and said: "There you can, with a dredge, recover more buffalo bones than the Indians will bring you in months!" Before leaving the subject of Dakota lakes the reader will be interested to know that on a visit to this section after thirty-five years, the writer drove across this lake in an automobile, where he had often, in the old days, steered the steamer over its waters a distance of fourteen miles between ports. And the water had receded from its old boat-landing docks, a distance of six miles, and the steamer skeleton lay more than 150 feet above and away from the water's edge; more than eight miles away from its old tying-up place. |

|

| Heerman Steamers, Devils Lake. The author rode these steamers each two weeks between Devils Lake and Fort Totten (1885-1886, often acting at the steering wheel for Capt. Heerman, the owner. It was 14 miles from the pier just below the Elevator and Railroad Siding connected for shipping, transfer, etc. Here again in 1910 he was driven across the same route in an automobile. In 1920, visited Capt. Heerman, and went to see the large steamer, a wreck, which lay 152 feet above the water's edge. The lake had receded six miles from the old pier. |

|

Today this region is an important part of the nation's breadbasket;

threaded throughout with railroads and covered with prosperous farms

and towns. One who has not seen this wonderful change can have little

conception of how and what took place in frontier days; nor can he have

a true conception of United States western history. Now let the reader

try to see, as the writer saw, this vast territory literally covered

with whitening buffalo bones, the result of the last years of the

hide-hunters' war of extermination of the northern herds, for in that

spring of '85, was the last to be seen of the wild native animals in

all the west; and it was the first of the starvation period for the

Indians in that section. The old hide-hunter told that the previous

season there had been two hundred and fifty thousand hides shipped from

one headquarters station on the Northern Pacific railroad, which he had

little trouble to at least partly verify by pointing to a pile of

bones, which later was found to contain two hundred and fifty

car-loads, which had been gathered and piled up at the west end of the

lake, waiting for the branch railroad to be completed to that point. In

making tours about the country for cattle buying a much larger pile of

bones was found at the Mouse River where the 'breeds and Indians had

collected them, far in advance of any shipping facilities; this pile

turned out over three hundred car loads, when the railroad came, and

there was another of about one hundred and fifty cars at Fort Totten. With the completion of the slaughter of the remnant of the great Northern herds in '84-'85, the suffering of the natives grew apace; they had no meat; no source of further supply of robes for tepee covers; no soft-tanned skins for clothing nor the warm furs to sleep on and under in the severe winters. It was pitiful to witness them shiver in the cold, and become gaunt and hollow-eyed from hunger. It was heartrending to watch an almost naked squaw in a desperate encounter with half- wild hogs as she tried to recover the entrails from a beef, which had been swept into the corral from the slaughter-house floor; she was at a disadvantage in having to work through barbed-wire enclosure, but she did succeed in dragging part of them out and made haste to her shivering children who stood waiting nearby in the snow. This the writer saw. A pathetic sight was the old squaw who sat behind a few brush which she had set up for a windbreak, and fished all day through a hole cut out in the ice for a chance pickerel to keep her family from starvation. But the white folks were busy with making money in this new country of new and varied opportunity; they were not interested in Indians—that was a matter for the Government, they said, and ignored the helpless suffering natives when they saw them; there were no welfare societies then, and the Government was far away. Like the buffalo, the native tribes were thus set on the way to extermination. Of course the buffalo-bone traffic was not limited to Indians and the French half-breeds. Land seekers, traders, promoters, real estate dealers, lumber-and-machinery dealers, all had a hand in the buffalo-bone trade when and wherever it was to their advantage. In the earlier years of the trade, in more southern regions, the homesteaders found the bone business of aid to ready money for land-office payments, living expenses, and to tide over, in periods of grasshopper ravages or drouth. White settlers were, as a consequence, responsible for, and carried on the bone trade over the southern sections; roving bands of Indians had not yet reached the starvation period, nor where they inclined to that sort of necessary labor; neither were they equipped for it, if they had been so inclined. In his charming book "My Life as an Indian" —a volume which everyone interested in the story of the extermination of the buffalo and of the life of the old days on the frontier should read—the author, James Willard Schultz, tells of the rapid a decline of the buffalo herds in the upper Missouri country. Schultz went to Fort Benton in the late sixties as a boy under twenty; he took a fancy to the wild life, took to himself a Blackfoot maiden for his wife, lived with that tribe through the pre- railroad times and traded in furs and robes until there were none left. He saw and delightfully describes, the tide of civilization spread over that vast inland empire from the Missouri of Nebraska westward to and beyond the Rockies. Mr. Schultz and his partner Berry carried on trade with the Indians for many years collecting and shipping buffalo robes and furs. He writes of one of their most successful years in which they accumulated four thousand tanned robes which brought them twenty-eight thousand dollars—and that the years 1882-83 saw the end of their supply of buffalo skins, when but three hundred were obtained. Mr. Schultz states that in one season when the Northern Pacific railroad was completed to the Yellowstone, the white hide hunters piled up one hundred thousand buffalo hides for shipment to eastern markets, at stations along that newly completed division. From Nebraska Historical Society; excerpt from an article by Mari Sandoz: "Hard upon the crack of the rifle came the buffalo skinners, with their worn I. Wilson knives, long iron pickets and skinning teams. They slit the hide down the belly and about the neck, picketed the buffalo's nose to the ground and hitched the skinning team to a tab on the rough neck hide. At the crack of the whip the horses lunged forward, and the skin was off. A further picture of the early-day traffic in bones is furnished the writer by Helen M. McFarland, Librarian of the Kansas State Historical Society, who found it after close search, in the manuscript division of that institution. As the article was written by Arthur C. Bill to tell how he got his start, it is not only interesting, but of historic importance as no doubt he was a pioneer in the buffalo-bone business since his experiences date 1874-76. As this letter confirms the statement of Mr. George Beck, that his understanding always had been that the bone gathering business had originated in the northern Texas region, it is reproduced in full: "In the winter of 1874-'75 my cousin and I engaged in gathering buffalo bones from the prairies between Dodge City and Camp Supply, I. T. We purchased a yoke of oxen each, wagons, camp supplies, guns, ammunition, a pony and a saddle, etc. Government freighters hauling on way south were glad to haul for us on their return trip north. We piled the bones along the trail with our numbers on same. They hauled the bones to Dodge City and piled them along the A. T. & S. Fe tracks from where they were loaded into cattle cars and shipped to St. Louis to be used in refining sugar; their hoofs used to make glue; the horns to make buttons, combs, knife handles, etc. We received from $7 to $9 per ton f. o. b. for the plain bones, and $12 to $15 for the hoofs and horns. We had only one thing to watch out for, and that was a supply of water. We camped wherever night overtook us, turned our cattle out, hobbled our pony, turned him loose, made our beds down on the buffalo grass, got out our cooking utensils, consisting of a dutch oven, frying pan, coffee pot, tin plates, knives and forks, etc. We mixed our baking powder in flour and water, baking the finest, lightest bread you ever ate in our dutch oven, using buffalo chips for fuel. We fried our buffalo steaks and bacon, made our coffee, fried our sweet potatoes and Oh Boy! didn't it taste good after being out in the wind all day! We made good gathering buffalo bones—would often come to a place where the hunters had succeeded in getting a stand on the herd and would kill them all. The hunters watched for the leader before doing any shooting. The leader, always a cow buffalo, with a number of buffalo in her family, would be dropped in her tracks the first shot; then the whole herd would stand still for a while, regardless of how many were killed. Then another cow would take the lead; she was shot down at once. After that the whole herd would stand still and all be shot down. The noble beasts of the plains were slaughtered unmercifully, for no gain. The hunter realized but little for his share. Following the hunters were the skinners—skinning the buffalo and staking the hide to the ground, flesh side up; then came the rustlers, gathering up the pelts and hauling them to the railroads where they brought but little—seventy-five cents apiece or less. The buffalo furnished a living for the Indians of the plains. The Indians only killed the buffalo for use of food and raiment. His tents. his beds, his moccasins, his lariats, his thread and many other useful articles, not forgetting his food. The only good that came from destroying the buffalo was to rid the country of the Indians—if we may call that good." |

| A pile of Buffalo Bones collected by Indians at Fort Totten, Dakota Territory (1885) said to contain 150 box car loads |

|

|

It was not until the latter half of the bone- period, when the last of

the northern herds were being exterminated, and hunger came upon them,

that the mixed breeds got active and led in business of bone

collecting. From early historic times, the French voyageurs, courieres

duBois, trappers and other employees of the Hudson Bay Co., had been in

close contact with the Chipewayans, Assiniboines, Crows, Blackfeet,

Sioux and Cheyennes, whose territory bordered the British possessions.

For two centuries they had associated, were friendly, and intermarried

to establish hybrid people known as half-breeds and generally referred

to as 'breeds by the early settlers. The French pioneers were an

ingenious set, and lost no opportunity to turn a penny, and they were

expert canoemen, ready always to transport men and materials up or down

the Red River or on the lakes, for a trifling consideration. For dry

land transport, they devised and constructed the famed Red River Cart,

a vehicle without iron tires, bolts, nails or screws. To these all -

wood, high-wheeled and heavy conveyances, they harnessed and hitched,

with raw-hide thongs and ropes, whatever domestic beast they happened

to possess that was large enough to drag it along—a cow, a bull, pony

in shafts, or a team of two animals in -any combination, when the

cart's weight required more than one to haul it. With each in

possession of such an outfit, fifty or more of these mixed-blood

families would travel about the virgin prairies until their loads were

heaped high above the withe-bound frame body of the cart and weighing,

according to the cart, an average of five hundred to ten or twelve

hundred pounds of bones. Camping wherever they worked, they leisurely

wandered about through the summer months, making a trip to the shipping

point when they felt like it and had the requisite loads assembled at

the starting point. The writer's introduction to buffalo - bone buying

came with the arrival of one of these caravans (in early '85) when it

was his duty to negotiate with the owners, for their purchase and

shipment to market. Reviewing the subject at this time no better

description can be furnished for the better Understanding of the

reader, than to incorporate from letters written by him at that period,

the way the trade was conducted—and so the writer's

half-century-old-description is repeated. The buffalo-bone train is

coming; the old chief stalks along in the van of the slow moving

caravan, his blanket draped gracefully about his one shoulder and

waist; his long black hair plaited into two strands dangling loosely

over his breast; one hand clutching the blanket fold and in the other

the long stem pipe of redstone and beaded pouch, matching in brilliancy

and pattern, the moccasins on his feet. He is followed by his motly

tribe of tousle-haired breeds and straight-haired natives— men, squaws,

head-bead-banded maidens, boys and pop-eye pappooses; some on foot, and

some astride of ponies; some leading the patient, harnessed cow as she

tugged listlessly at her heavy load; others whacked the tough hides of

overloaded bull and tired pony to keep them in line, and mothers topped

out the loads with their blinking or sleeping babies, encased in

striped shawls, drawn close about the shoulders. Scattered along on

either side and in the rear of the long procession, were the loose

ponies, young stock, youths and dogs. As it was seen far out on the

prairie, it was like some interminable, wriggling, creeping sea-

monster which had been suddenly stranded, and was seeking its natural

element again. The hideous noises, which one might imagine coming from

such a leviathan would be something like that arising from the

greaseless, sundried wooden carts; noises intermingled with the crack

of whips, the yelping of curs and the clamor of vociferous drivers; its

weirdness might be likened to a horde of howling coyotes. Half a mile from the frontier town's border, the caravan is halted; a council of the chief and his leaders, is held while the squaws divest the carts and ponies of their tepee covers, camping paraphenalia, and collect the children and dogs, for it is the time and place for pitching camp. The little band of chief and his counselors form in line and march to consult with the young man who stands behind the glass in the front office of the brick building where the weighing machine is. Approaching the cashier's window and with dignified "How" the leader wishes to inquire what is the price for bones; and with awkward signs and aid of interpreter, the callers are informed that $6 per ton will be paid in cash. They retire to consult; they leave but in due time the screech of the crude freight outfit is heard as the long line of loaded carts move slowly along the street toward the weight-scales outside the office window. Cart No. 1 advances until it rests fairly on the plat- form; the scale is balanced and the gross weight recorded on a ticket, torn from its stub and handed to the driver who passes on, and cart No. 2 follows the same process, and so with all that belong to the train. By the time the last one has reached the scales, No. 1 may be three or four blocks away with the followers blockading traffic and attracting crowds, some curious and others critical. They dump their carts at the unloading ground at the railroad siding and reform the line of procession and proceed to the weighing scales where the same ceremony is repeated. This time the process is much slower for each ticket holder is to wait for the calculations to be made to arrive at the net weight and value of his load, and the cash paid to him; subject always to the verification of his interpreter or associate. The bones are then loaded into box cars and shipped to the St. Louis market. Freight rate from the region being $8 and later $10 per ton. Delivered at St. Louis, the bones were paid for at prices ranging all the way from $18 to $27 per ton. Railroads granted favorable shipping conditions and rates, as encouragement for first settlers to survive the test of endurance over the three or five years required to prove up title to their homesteads and pre-emption claims. In most cases that was a severe test. But we follow the train of emptied carts after the owners have received their cash at the office window. Where the squaws and children waited, there has been a new and important addition erected in the frontier town, doubling its former area and population; it is a cosmopolitan city comprising members of every color, creed, country, for it is the time of opening of the great Inland Empire. The tepees stand in irregular order over the level prairie to the east, north and west, beyond the town limits. The empty carts are arranged in a circle around the encampment; within their fence-like enclosure are loosed the ponies, cattle and dogs to rest and graze without too much attention for herding. Smoke from many fires tell of the preparation of the evening meal. Except for feeding animals and prowling dogs, one might believe the camp had been suddenly deserted, but soon the tepees are forsaken by their occupants, for family visits and recreation. The men gather in circles around a fire to sit smoking the long stemmed redstone pipes and discuss plans for the next expedition for bones. The women gather in little crowds to make plans for visits to the stores, while the children romp and chatter all around the grounds. For one, two or sometimes, three weeks elapse for these now happy folks to exhaust their funds in trading about the stores or engaging here and there at jobs that may be offered to earn a dollar; the women and girls, too, take house - work, cleaning offices and stores, to earn a little to help in living costs and to obtain food, muslin for tepee covers, and bright calicoes for clothing. Then as suddenly as they came, they disappear. Weeks pass. Then the same band will come again—and so the summers come and go with few days in which some outfit is not thus encamped at the frontier boom-town. Meantime the immigrants came in carloads and in train loads to equip themselves here with needed farm implements, furniture, food and seed supplies, oxen, horses and wagons — and most essential, lumber for erecting the new farm houses. Daily they leave there, singly and in small parties, long strings of settler families thus provided, for taking up the raw lands for future homes. Talk of the extension of the railroad continued. James J. Hill had been dreaming of an Inland Empire for the now deserted buffalo range; he would re-establish herds of domestic cattle in their lush pastures, and to that end imported black poll-Angus pure-bred stock for distribution among the hordes of incoming Laps, Fins, Norwegians and other Europeans. This was a hardy breed, and looked not unlike the native buffalo, and could stand the cold of severe winters. Great preparations were made for the mid-summer fair, where these purebreds were to be on exhibition. A race track, with stockade surrounding it, was built; races were booked in which trotting, running, pacing and stunts were provided; cowboys and Indians contested in roping, and bronco-busting. Special trains brought great crowds from Minnesota; the steamer was weighted down with troops and traders and natives from the fort; farmers came from far and near in "covered" wagons; bands paraded the streets crashing circus music constantly; hotels and hot-dog stands did a thriving business—and the saloons reaped a harvest. The writer was commandeered to act as treasurer for Mr. Hill's first big demonstration, to justify the extension of his railroad into the vast undeveloped "boneland" which lay to the west. And it was a huge success; money poured in so fast as to require a distress call from the treasurer for extra valises, boxes and bags, to handle it. It was likewise a great success in furthering Mr. Hill's plans. |

|

Talk of railroad extension finally took a practical form. Contract was

let for pushing the tracks toward the Mouse River far beyond, where

settlers were making homesteads, but already the widening circle of

settlers had spread to the north and westward, compelling the 'breeds

and Indians to reach farther and farther out to obtain their supplies

of bones. On filing for his 160 acres, the homesteader forbid the

natives to trespass; he would gather his own buffalo bones. Constantly

crowded back, as the natives thus were, they continued the only means

they had for obtaining a revenue sufficient to sustain life. Toward the

end of the trade at this point, these poor people gathered and hauled

their cargoes one hundred and fifty miles over unbroken prairie and

around the lakes, sloughs, and plowed quarter-sections of settlers, in

order to get the pittance their loads might bring. During this period,

and long before the railroad reached the upper Missouri country, vast

quantities of buffalo bones were gathered from the Montana ranges and

shipped by boat from Fort Benton and other points, to Bismarck and

there shipped by rail to market. By the early nineties, bones were

being gathered and shipped out of British possessions north of the

border. North some ninety miles from the railhead lie the Turtle

Mountains at the Canada border, which at that time was an Indian

reservation. It was a wooded section and contained and was refuge for,

a considerable remnant of big game and fur - bearing animals.

Immigrants, in their greed for securing some of this rich wheatland,

frequently went far into the open range and staked out their claims,

without taking into consideration the need for fuel for the bitter

winters. They encroached upon the forests belonging to the Indians;

they cut their timber; trapped their fur-animals and hunted the deer

and game birds. The native tried to protest but could find no answer to

their complaints. One Sunday morning before break of day, the room-mate doctor, in from a late call, rushed to the bedside of the writer and woke him saying: "Get up quick, the Indians are out there; they are holding a war-dance; they mean devilment and will burn the town; hurry, and see what you can do with them !" The writer was the "Indian" man; he knew the Indians, and they knew him; and knowing his responsibility, in dealing with them and seeing to their good behavior when in the white man's town, no time was lost in dressing, grabbing a six-gun, and going to the place where they had been seen by the doctor—a mile beyond the town. The warning was justified, for in the fading darkness could be identified a band of the Turtle Mountain natives numbering some 100 to 150 men; they were holding council, apparently not fully determined what to do; there was loud talk and angry threats. As the youth advanced to learn what it was all about, he encountered Chief Little Shell, took hold of his arm and got him away from the excited crowd where, after a short talk, he was induced to accompany the youth back to town, where the doctor waited at the street's end to carry messages or render first aid if needed. Here the anxious friend was sent to arouse the fruit-store proprietor who came promptly and opened his shop. The Chief was treated to cigars, candy and fruit until his blanket bulged with them; a window - shopping trip was made where things unknown to the red man were explained—it being the plan of the young man to hold the leader out of sight, or communication with his tribe until the troops could be notified at the Fort, or secure from him his promise to take his troubled people back to their home in the mountains. The itinerant picture-taking wagon had come in a few days ago, and was standing at the end of a side street tightly closed. The light had become strong enough to get a tintype of the Chief to present to him, if the proprietor could be found. Doc was available and went on the hunt. The wagon - gallery man unlocked the door and arranged for the "sitting." When adjusting the focus by raising the black cloth light-shield over his head, and exposing the brass-capped lens, pointed directly at the face of the Chief, the frightened Indian sprang from his seat and out the door. It took time for the young man to allay his fear and assure him that no harm would come to him. A second trial was more successful; the "artist" posed the boy in the chair. Then he got the Indian to stand at his side; then being assured that if the little brass cannon went off, the bullet would hit the boy and do the Chief no harm, he stood quiet until the necessary exposure was made. On presenting to the astonished Chief his own portrait, the boy was able to exact the promise from him that he would now go back to his leaderless little army and assume command. On the promise of immediate attention from the Washington authorities to stop the settlers from stealing their timber and killing their game, he agreed to order his warriors back to the reservation. The Chief was then guided through the streets, lanes and alleys, to the opposite side of the town, and to the place where his tribe had been unceremoniously abandoned before daylight. A final handshake, and the Chief's order started the unhappy and disappointed crowd on the trail leading to the reservation. It was all over before the town folks stirred about after their late Sunday morning breakfast; and over their own late breakfast, the doctor and the writer decided best to say nothing, to avoid publicity, for it might interfere with business, and perhaps bring the wrath of Custer's troops at the fort, against the suffering natives, and so the incident was closed and soon forgotten —forgotten except for the life-long humiliation at failure of the Indian Bureau to intercede for and protect the rights of these abused natives. With the end of the three-year period of 1884-'86, the bone traffic in the north-central area of Dakota Territory became less in volume and importance; the trade centers were carried west with the extension of the railroad and the influx of homeseekers. Church's Ferry, Rugby, Towner, at the Mouse River, Minot, fifty miles beyond, all had their shares of the buffalo bone business and each contributed its proportion to the grand total. And this was repeated over that long open section from Berthold to Fort Buford at the Yellowstone; through the Fort Peck region, and up the valley of the Milk across the northern two thirds of the great state of Montana, to the Blackfeet country at the base of the Rockies. By the boats of the Missouri, and the Northern Pacific, bones had been pouring out of the central and east sections of Montana since the early eighties, but the stream from its northern area continued into the early nineties, as the business gradually slackened and disappeared from sight and memory. Lumber being the first requisite for making habitable the treeless wide plains country, wholesale dealers in lumber and building materials were the advance agents on every frontier as the tide of immigration spread through the northwest regions of the buffalo-Indian country. They had their sheds and yards at every railroad station, and at every likely town-site to where stock could be transported. And in trade for lumber and supplies, they accepted buffalo bones, and it is of record that one of these lumber firms shipped an average of a thousand car loads a year over the seven years 1884-1891, from the northern Dakota district. This firm stated that each car load comprised the bones from eight hundred and fifty animals, thereby accounting for 5,950,000 buffaloes. It is safe to suggest, that during this same period, there were hundreds of other such agencies and merchant-traders doing likewise in the same region. Some years after the bone trade had ended, the writer consulted Mr. George Back, then President of the Empire Carbon Works at St. Louis, with regard to the tonnage used there. He said that about seventy per cent of the buffalo bone shipments had been processed at that city; the remainder of which trade went to Philadelphia, Baltimore and Detroit and other eastern factories; and the price paid for them delivered f. o. b. had ranged from $18 to $27 per ton, and records then immediately available to him showed that his plant had taken more than one and a quarter million tons, which, at the rate of his average price, or $22.50 per ton, would show $28,125,000. Assuming these estimates to be reliable, as they no doubt are—and fairly accurate—we readily arrive at a total sum of over forty millions in money value, for the total industry—a rather sizeable pay-roll to have escaped the notice of history writers. After the lapse of half a century, as this is written, the recollection of the purchase from the poor natives of thousands of tons the bones as the last miserable resource left them after suffering the loss of their only means of existence, by the ruthless hidehunters, brings a pang of remorse. It was a heartless exploitation of innocent and helpless people to pay them $6 a ton, and without other expense than the loading of them into box cars, bill them out at $20. However, it is a satisfaction in some degree to recall that none of that unjust profit came to the writer. Instead, he always contributed to making their lives a little more cheerful, when and wherever possible — and that has continued to the present day. There is no honor among many he has received, so highly valued as that solemn ceremony performed by famous chiefs many years ago in the presence of Col. W. F. Cody, making the writer a Chief of the Sioux. |

|

|

Personal letterMr I. McCreight:- Dear Friend- When I was up north this summer Ray told me that your statement concerning the bone industry was questioned. Well, I can substantiate what you have written. Many times while living in North Platte, Neb., I saw piles of bones as high as a cottage on a vacant lot near the heart of the city. Frequently passed them on my way down town. Also know that people used "buffalo chips" for fuel. I was very much interested in your book. In fact all of your writings have been very interesting and truthful. I have always been in sympathy with the American Indians, and thought you should have been the head of the Agency. Hope you are all well. Kindest regards to the family. Sincerely your friend, Emma O. Stumpf 1801 Richardson Place Tampa, Fla. |

| Offered July 2008 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

| home | ||

|

|

||